Categories

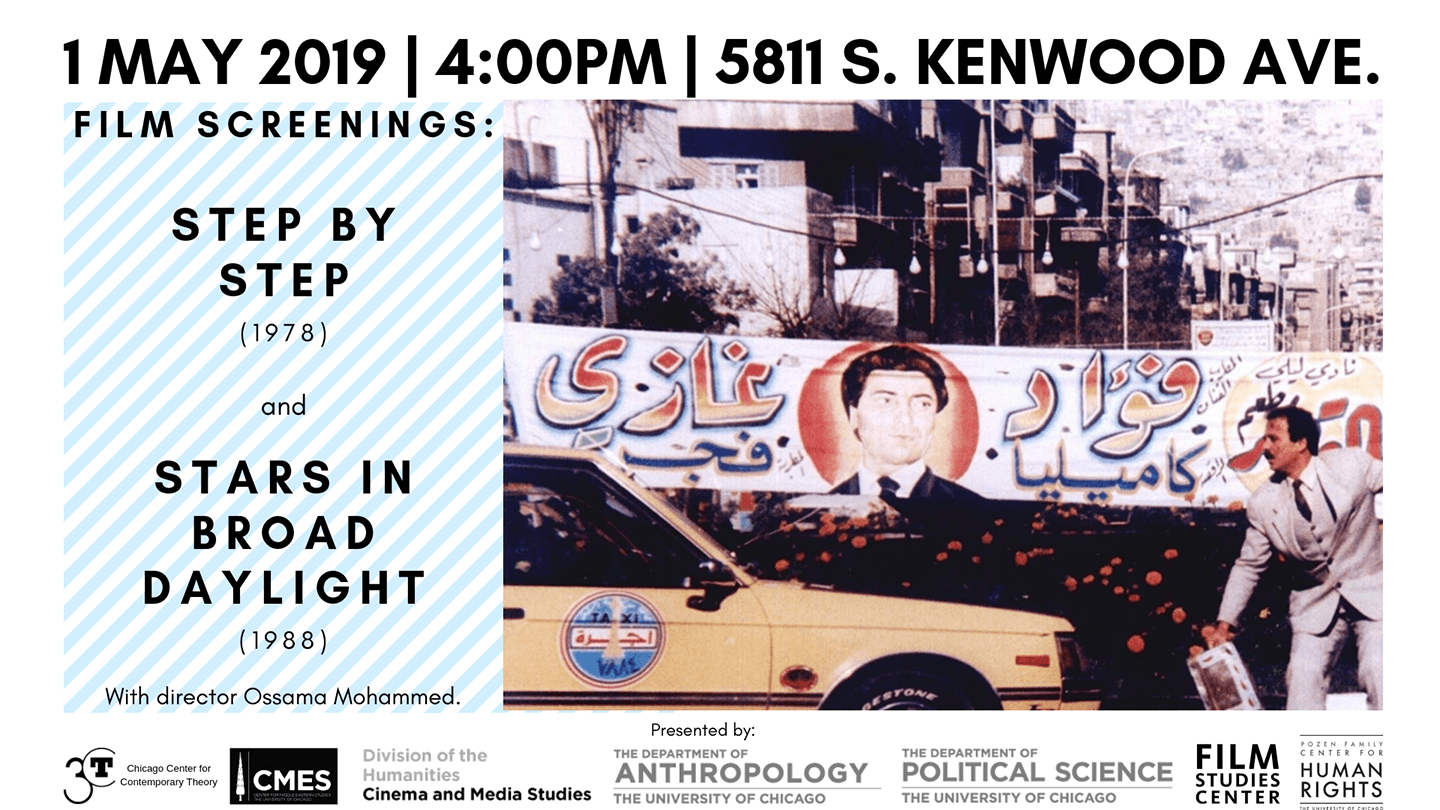

Ossama MohammedFilm Screenings: Step by Step, Stars in Broad Daylight

Wednesday, May 1, 2019, 4:00-6:30pmPlease join 3CT for screenings of an astonishing documentary short, Step by Step (1978) and a feature-length parody of regime rule, Stars in Broad Daylight (1988) by critically-acclaimed filmmaker Ossama Mohammed.

This event is co-sponsored by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, the Department of Anthropology, the Department of Cinema and Media Studies, the Department of Political Science, the Film Studies Center, and the Pozen Family Center for Human Rights.

Ossama Mohammed is one of Syria’s most important directors, whose auteur style of filmmaking is responsible for films ranging from trenchant, dark satirical commentaries of regime rule to quasi-documentaries that defy conventional genre distinctions. Nujum al-Nahar (Stars of the Day, aka Stars in Broad Daylight, 1988) is perhaps the most politically critical film ever to have been made in Syria. An insightful and revelatory critique, the film’s plot is a thinly disguised metaphor for political power and for the now deceased President Hafiz al-Assad’s ‘cult’ of personality. In the film, Mohammed depicts the moral crisis of a rural ‘Alawi family, some of whose members have moved to the city and succumbed to urban life and corrupt officialdom. As characters, they represent the regime’s vulgarity and brutality. The main male protagonist – who looks uncannily like the former ruler – is the controlling, manipulative, stingy brother and the de facto patriarch of the family, an association that explicitly connects patriarchal family life to martial rule and political violence. Drawing on his intimate knowledge of sectarian and regional specificities, Mohammed parodies the emptiness and tedium of official discourse, at the same time lamenting the beautiful but ultimately unlivable countryside. Overrun with petty familial disputes and patriarchal violence, rural life offers no refuge, even while collective fantasies of national belonging have themselves been reduced to vapid slogans – devoid of the hope or sense of community that animated the early days of post-colonial rule. These themes – patriarchal violence and rural disrepair, in particular – also motivate Mohammed’s stunning and brave first film, Khutwa, Khutwa (Step by Step, 1979), an experimental work he completed for his MA in Moscow. In this first major effort, Mohammed blurred the conventional boundaries between documentary and fiction, producing a poetic tour de force whose aesthetic and political sensibilities have continued to inspire new generations of Syrian filmmakers.

Mohammed’s attention to the juxtaposition of beauty and violence in everyday life also finds expression in Sunduq al-Dunya (or Camera Obscura – oddly translated as Sacrifices in the English version, 2002), another account of familial conflict in Syria’s coastal countryside. Less overtly political than Nujum al-Nahar, Sunduq al-Dunya focuses on a grandfather who wants to bestow his name upon one of his three grandchildren but dies before fulfilling his wish, consigning the children to a life of namelessness. Each grandchild finds meaning and pleasure in different ways over the course of a quasi-allegorical tale of human frailty, political power and the seductions of violence. The first child practices restraint and composure, the second, love, and the third, cruelty and caprice. Again we see power corrupting, even as the countryside, the filmmaker and the audience bear witness to life’s beauty and brutality. Symbols of fecundity and openness suggest the power of regeneration, while simultaneously producing a sense of being boxed in, not unlike an actual camera obscura, in which light from an external scene passes through the aperture into an enclosure, generating an inverted image.

In all of his films, Mohammed uses the symbols and language of political power to subvert official systems of signification. He brings to his cinematic object a profound sense of displacement borne of his knowing a place extremely well. This displacement has now found tragic expression in the director’s own forced exile since 2011, as well as in his artistic efforts to grapple with the shift from peaceful protests to catastrophic war.